In a recent post, I talked about the importance of embracing both usability and usefulness in user-centered design in order to ensure the market success of a product. I argued that you have to acknowledge that you don’t know everything about your user that may impact your design and you have to have a willingness to change that, by refining and expanding your understanding.

So how do you go about doing that? By committing your project and team to the user-centered design process, which starts well before any concepts are drawn or solutions are prototyped.

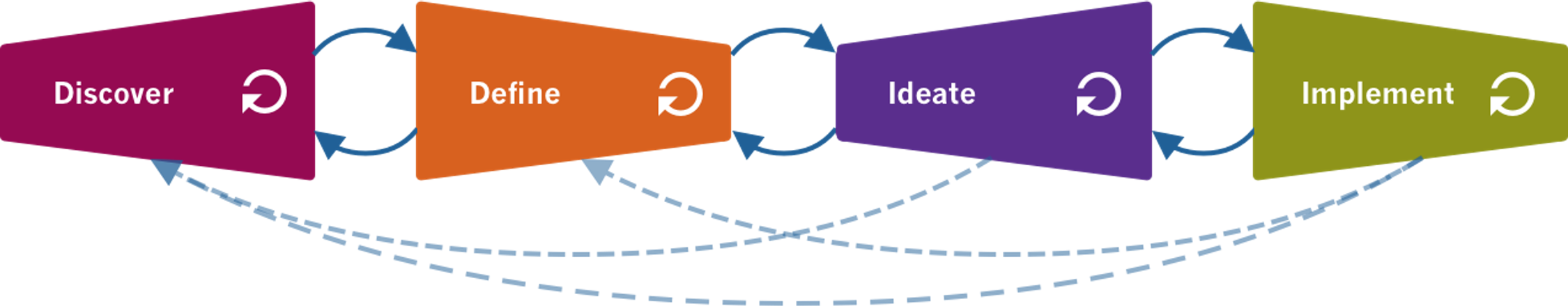

There are four basic phases in user-centered design:

Notice that the phase in which you start ideating solutions doesn’t happen until the second half of the process. It’s only in the latter half that you move into exploring the solution space. The first half of the process lies in discovering and defining the problem space.

In user-centered design, the first phase is discover. It’s a process in which you frame the problem you are trying to solve and then conduct secondary and primary research to ensure that you truly understand that problem and the users you are trying to solve it for. This phase relies on generative thinking — thinking that is expansive and that helps you to make discoveries, produce new ideas, and develop new theories to understand your problem space.

The first step is Problem Framing, which is simply making some early choices about the boundaries of your project, how you’ll define its success, and the people and issues that you need to study and investigate.

To frame the problem, you pose questions such as:

- Are we creating an entirely new experience? Or modifying an existing one?

- Who are our users? Are they novices? Perhaps someone newly diagnosed with a medical condition that our product is intended to treat or manage? Or are they experts? Perhaps a nurse with 20 years’ experience in the area we are looking at? Maybe some of each? Are there other users that we need to consider, like maintenance or support personnel?

- What are the primary goals of our different types of users and how do those goals break down into subgoals?

- What are the decisions that our users need to make and what information do they need to make those decisions?

- What are the specific environments and use scenarios that need to be addressed?

- Do we have an idea of what might be some of the barriers that our users are facing?

Once we’ve properly framed the problem by asking these initial questions, it’s time to answer them via research. There are two very broad categories of research used in user-centered design: primary and secondary. Primary research directly involves your users via observation and interviewing, whereas secondary research involves exploring existing sources of knowledge that may help to answer these and other questions (it is one step removed from your users, hence the term secondary).

Paradoxically, we start with secondary research. Secondary research can involve benchmarking competitor’s offerings and industry trends, and exploring tangential industries that may provide potential solutions. For example, for our fall safety harness, we ultimately borrowed buckles commonly used in car roof rack systems for our design, which greatly improved ease of use. Secondary research should also involve mining data that is already available to your company from departments such as marketing, IT, or sales. Consider interviewing customer service representatives or searching your company’s service database to learn about customers’ pain points. Ask installation and maintenance teams about the different user environments or innovative uses of equipment they may have seen or interesting requests they may have gotten from users. Talk to salespeople about what matters to their customers and why other potential customers aren’t interested.

Regardless of what you learn from secondary research, it is critical to conduct primary research, in which you interview and directly observe your users. Primary research is first-hand research. It is exploratory and immersive and provides insights into what users actually do, how they think, the choices they make, and what influences those choices. It allows you to view activities in their context of use to explore how other tools, other people, and even the environment impact those choices. It allows you to learn what it is that you don’t already know.

Yes, these activities will add a few weeks to your schedule. But they lead to better upfront identification and analysis of user needs, which leads to clearer criteria development and higher team confidence that the right problem is being solved. Taking time to ensure that you understand what it is that your users actually need and want is far more profitable than being quick to market with a product that won’t succeed because it doesn’t captivate your users or fails to address their unvoiced reality. It’s also more profitable than being late to market because of delays caused by late project learnings and the associated late project changes.

Daedalus is adept at discovering users’ needs, and at the remaining phases in the user-centered design process, which are 2) Define, 3) Ideate, and 4) Implement. We’ll be posting articles in the upcoming weeks for each of the subsequent phases.