My mom is barely old enough to remember a world without color television. As far as I remember, we’ve always had a computer in the house, and my younger brother never knew the pre-internet world.

Technology, its advances and accessibility, revolutionizes the way we live. Because designers play a key role in the way transforming technologies are implemented, they shape our everyday experiences. Designers have always created experiences — whether technologically loaded or lacking, intentional or unintentional, direct or indirect, good or bad — but along with technology, the definition of experience has also morphed throughout the years.

I recently (about 4 months ago…so maybe not so recently) attended the Midwest User Experience Conference in Columbus, Ohio. The ending keynote was given by Richard Buchanan, Professor of Design, Management, and Information Systems at the Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University. His presentation “Experience, Human Interaction, and Service Design,” left me contemplating what experience is and how a designer affects it, especially as technology becomes more prevalent.

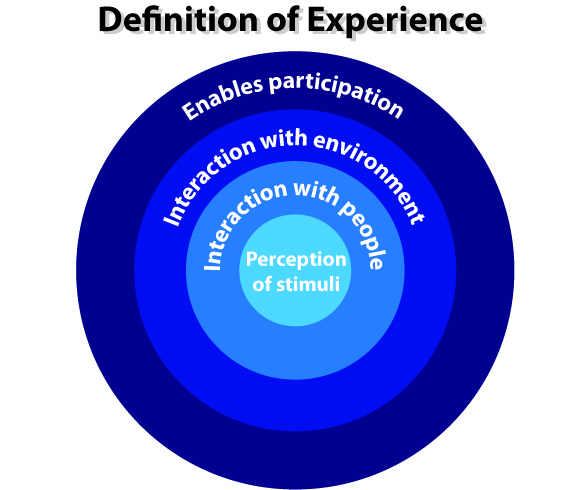

From Buchanan’s perspective, for the earliest industrial designers experience meant the user’s perception of the stimuli created by the object itself. It was about the direct interaction between the product and the user. His discussion of this brought to my mind Charles and Ray Eames, whose furniture designs were conceptually backboned by “the search for seat and back forms that fit the human anatomy” (Library of Congress, 2010). They were concerned about anthropometrics – the human body’s relationship to their product – and were designing the users’ experience of sitting in a chair.

Beyond the relationship of people to things, Buchanan then illustrated how the term experience within design soon encompassed the relationship of people to people. Designers thought beyond the user-product experience to how their product would enable or affect human interaction. In other words, how people could relate to other people in meaningful ways. For example, email allows you to send and receive messages near-instantly. Nearly two decades later, AOL Instant Messenger became popular – you could literally carry on a conversation in real-time while sitting at a computer. Yet, despite the increased interaction, you were still “talking” to a machine, eliminating most human elements. This changed with Skype. I remember my sister showing me her University of Montana college dorm room as I sat in Virginia. I was able to interact visually and aurally with a loved one across the country in actual time, creating a much more meaningful experience than typing on a computer or listening on a phone.

Returning to Buchanan’s ideas, he explained how experience then expanded to include how people interact with their environment. He used John Dewey’s book, Art as Experience, to illustrate this point. Dewey argues that the fundamental element of a work of art is not the material or form, but rather the development of an experience. While looking at a piece of work, the observer sees not just the physical art, but also encounters the artist — their thoughts and culture. The piece enables an experience that goes beyond the piece itself. Hence, two people can look at the same piece of art and have totally different experiences (Art, 2012).

After defining experience as the interaction with 1) stimuli, 2) other people in meaningful ways, and 3) the environment, Buchanan then offered a new perspective on the meaning of experience. He suggested a fourth order of the word — the relationship of people to participation, or enabling participation.

He asked the audience to think about this for a moment. What does it mean to enable participation? How, as a designer, do you do that? It begs us to dig deeper — to really know the user; to know the values and intentions of the people you’re designing for; to know what information means to people in their settings. You can’t just design a comfortable, convenient, easy, simple, or whatever-adjective-desired type of service or product. You have to saturate yourself more fully into the users’ shoes, really understanding their core values and desires. And you must go beyond the user(s) to the organizations and systems that they’re a part of. You have to ask: how can the work of a designer help people reach their potential? How can it help people be more human?

That is the question that started my wheels turning. How can designers design experiences that help people be more human? That the question was even asked caused a flood of thoughts to rush through my mind.

I see automation becoming the norm — and I don’t mean that I foresee it — I see it happening all around. Machines are doing a lot of the work that humans used to do – physically and mentally. On a busy Saturday afternoon at the grocery store, there used to be a number of cashiers checking out customers. Now, self-service machines have replaced a lot of them. To rent a movie, you no longer even have to speak to another human being — just use the ever-popular Redbox. Companies and organizations no longer need secretaries to answer the phone; it’s all automated. We have apps that lock our doors, coffee machines that make our morning cup of joe, and lights that turn on or off by sensing movement. We text rather than call, email coworkers rather than walk across the office, shop from the comfort of our living rooms rather than run to the mall. Take me for example, I no longer remember family or friends’ phone numbers. I don’t need to — they’re all kept on my speed dial. I think we have to ask ourselves: are we becoming lazier? Dumber? In any way, less human?

I’m not against technology; I’m not suggesting that it hasn’t made our lives more convenient or that there isn’t a use for it. In fact, I see technology as supplementing humans — allowing humans to be concerned about the things that matter and not expend effort on the little things that don’t. But do we really know the implications of giving up those supposedly minute tasks? Is our hunger for convenience robbing us of our human experiences? For example, because I no longer need to remember phone numbers, will my short-term memory span decrease comparatively over time? Could we eventually lose the skills that allow us to commit those phone numbers to memory?

Buchanan’s prediction that experience will soon primarily mean designing for participation, suggesting a paradigm shift in the designer’s thinking, implies one thing in particular — that participation is a key element to being human. If we decrease our need to participate, we slowly erase one of the core needs of humanity. If this is true, then so is the inverse — if we increase participation, then we better satisfy a core need. Maybe this is why we’re seeing a new trend within design research techniques — moving from solely user-centered design to co-design, in which people not trained in design (i.e. users or participants) co-create throughout the design development process with designers. Thus, they no longer simply inform design decisions but make them. So as designers, we must define (or redefine) participation. We must be aware of the fine balance between edifying and degrading the user’s experience through technology (or lack thereof).

All in all, there are no answers, just more questions leading to more unknowns and what-ifs. These questions can be debated over and over, with numerous examples to dispute one argument over another. But it does, or at least should, make you stop and think about humanity. About technology. About their intertwinement and shaping of experience. And about the designer’s role amongst it all.

____________________________________________________________________

Art as experience. (2012, May 20). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_as_Experience.

The Library of Congress, (2010). The Work of Charles and Ray Eames. Retrieved from website: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/eames/preview.html.