When Daedalus was sponsoring the Pittsburgh Technology Council’s event The Creative Technology Network’s Innovator Series Presents Roger Martin: Gaining Competitive Advantage with Design Thinking (5/22/2012), I decided to read Martin’s The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win through Integrative Thinking.

Martin, a leading business speaker and thinker and a global Design Thinking evangelist, is Dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, a former director and co-head of the Monitor Group, and was a key advisor to A.G. Lafley as he transformed Proctor & Gamble into the creative company it is today.

This particular book is a detailed discussion of the concept of integrative thinking, defined by Martin as:

…the ability to constructively face the tensions of opposing models, and instead of choosing one at the expense of the other, generating a creative solution of the tension in the form of a new model that contains elements of the individual models, but is superior to each.

The phrase that piqued my interest was “generating a creative solution.” Last month we posted Why Ordinary Brainstorming Doesn’t Work in response to several recently published articles that disparage brainstorming – these articles claim that it doesn’t work, but don’t delve into why it doesn’t work. We outlined the problems that we see with conventional brainstorming. It was based in part on a Lunch & Learn held at our office during which we not only explained why conventional brainstorming fails, but also introduced participants to more successful idea-generation techniques. So, naturally, I was intrigued to explore Martin’s theory in more depth.

Parallels Between Conventional Thinking and Conventional Brainstorming

As I read The Opposable Mind I was struck by several parallels between the limitations of what Martin refers to as conventional thinking — as opposed to integrative thinking — and the limitations of conventional brainstorming that we had detailed in our article.

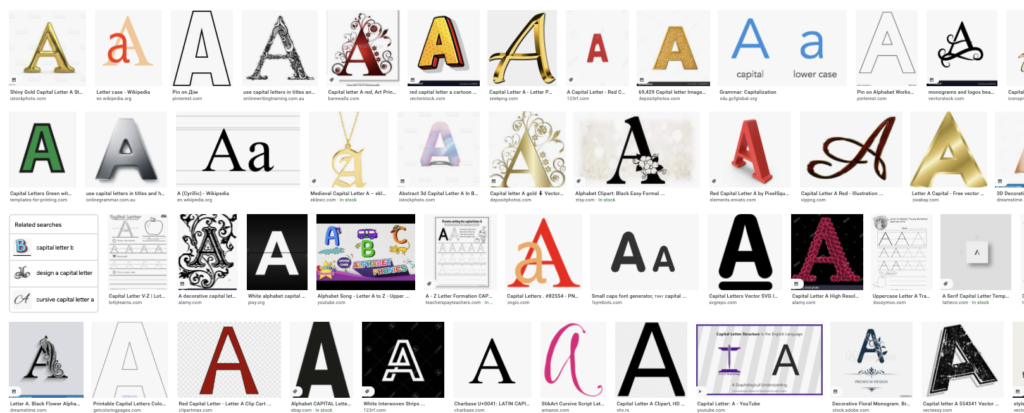

The first to catch my attention was a comment from Martin that specialization discourages integrative thinking. Martin classifies specialization as a form of simplification, another process detrimental to integrative thinking. Simplification — simply put — is the human way of making sense of what happens around us without being overwhelmed by details. It’s a well-known phenomenon in human information processing theories of cognitive psychology — my field of study. For example, consider the picture below of a Google Search for the letter “A”.

You have no trouble recognizing all of these images as uppercase A’s, though they are each quite different. You are able to filter out all of the extraneous details and focus on only those few features that make up the letter A.

The same applies to our decision-making process. Consider when you bought your house, for example. Any two houses will differ in hundreds, if not thousands, of ways: the number of rooms, the number of bedrooms, the number of bathrooms, how many levels, is there a basement, a garage, walk-in closets, a laundry room, skylights, the size of the front yard and backyard, the distance from work or to your kid’s school, is there a school bus route for your kids, the size of the deck or patio, how many outlets are in each room, can you get cable TV, can you pick up satellite TV, what type of heating and cooling, is the stove gas or electric… This list goes on and on and on. If you were to compare even just two houses in all of the ways that they differ, you’d have never been able to make a decision. There’s simply too much information to process — the cognitive workload is too high. So we simplify. Just as we know what features are important to make an A, we also determine what features are important for our decision and ignore the rest. The ones we pay attention to are the “salient features” that Martin discusses – another concept drawn from cognitive psychology. The problem, Martin argues, is that there’s important information mixed in with what we choose to ignore, which limits our ability to devise creative solutions to the problem at hand. Specialization is a form of simplification; the specialist becomes highly knowledgeable about a narrow range of features — those that are important to the specialist and his/her chosen field.

So what does this have to do with brainstorming? We argued in our brainstorming article that one of the failures of conventional brainstorming is the lack of diversity in the participants. Too often corporate brainstorming sessions invite people from the same department, who possess the same skills and because of that — have the same experiences. Most likely, these are people from the same specialties, and they have likely already reduced a myriad of data points to the same set of salient features. They are likely to follow the same logic path and reach the same decision. We argued that one of the keys to innovation is diversity of experience, and it is this diversity that Martin also argues allows a solo decision-maker to recognize the importance of the data that the rest of us typically ignore.

We argued that another problem with conventional brainstorming is that often participants are told that the “sky is the limit” – no constraints are placed on the session. The problem is that creativity thrives on constraints. So why tell participants that there are none? My belief is that session organizers don’t want to burden participants with understanding how an idea might affect all of the other details in the mix – in other words, the cause-and-effect relationships involved in whatever the problem at hand. However, Martin argues that it is vital to integrative thinking to not only be aware of these relationships but to explore them in greater detail. He argues that conventional thinkers tend to see only the linear relationships that exist among the features that they choose to pay attention to, whereas integrative thinkers recognize the non-linear and multi-directional causal relationships. Integrative thinkers, therefore have a much more developed understanding of the constraints for the problem they are trying to solve, which helps them to devise solutions that work within – or even nicely side-step – those constraints.

Martin also discusses how the ways in which an integrative thinker organizes the salient features and information about complex causal relationships differ from that of a conventional thinker. The integrative thinker’s mental model of the problem — their internalized representation of it — more closely matches reality. The problem is that conventional thinkers – most of us – not only focus on a narrower set of features when making a decision, but we also have a tendency to seek out information that supports our preconceived ideas of the problem. Psychologists refer to this as the Confirmation Bias. Intrinsically, we don’t want to come across data that negates what we believe to be true – it causes us additional mental work. So we have a tendency to not perceive that which does not fit our worldview and the decisions that we’ve already made. We don’t see the world as it is, but as we believe it to be. I see this as akin to the concept of Hidden Agendas, which we discussed in our brainstorming article. Not only might a participant be wary of ideas that may be perceived as detrimental to that participant or his department, but that participant may have a great deal of difficulty simply understanding and judging the merit of an idea that conflicts with his or her views of the company, the market, or his or her department.

Looking back on this article, I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised by the parallels between our conclusions about the failures of conventional brainstorming and Martin’s conclusions regarding what stands in the way of integrative thinking; the goals of both are also in parallel – to reach a creative and innovative solution that has not been previously been considered or explored.